As the WNBA Centennial approaches (see the event breakdown here), it’s a great time to remember not only why books are important to you as a WNBA member but also to society. Book lovers are often asked to validate their appreciation for books. It can be hard to respond to an argument that books don’t matter even though there’s a breadth of evidence to the contrary, so, if you ever find yourself confronted with an individual arguing against literature’s social impact, take an example from war poetry one hundred years ago.

As the WNBA Centennial approaches (see the event breakdown here), it’s a great time to remember not only why books are important to you as a WNBA member but also to society. Book lovers are often asked to validate their appreciation for books. It can be hard to respond to an argument that books don’t matter even though there’s a breadth of evidence to the contrary, so, if you ever find yourself confronted with an individual arguing against literature’s social impact, take an example from war poetry one hundred years ago.

1917: The ongoing, and seemingly everlasting, entrenchment of forces during the then-Great War (now World War I) increasingly demoralized soldiers. Though the United States was new to the war, entering on April 6, 1917—over two years after the war commenced—English soldiers were (to put it mildly) unenthused about the continuation of the war because of the high casualties and continuing stalemate on the Western Front.

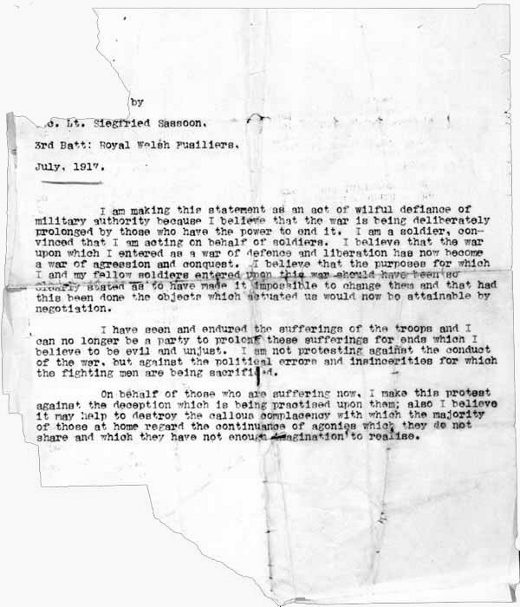

Sassoon’s Letter

Courtesy of Wikimedia

One such soldier, Siegfried Sasson, had been nominally a poet before the war. His time on the front inspired him not only to write influential war poetry including “Dreamers,” “The Dug-Out,” and “The General,” but also to publish a letter in the London Times in July 1917. This letter was titled “Finished with the War: A Soldier’s Declaration,” and, in it, he refused to return to the front as well as accused that the war was “being deliberately prolonged.”

Sassoon’s declaration was unacceptable for public morale. Because he was a decorated officer, his published letter could not be ignored, so the army removed him from the public eye by sending him to a hospital for “shellshock.” At the time, PTSD wasn’t a diagnosis—shellshock was. Until then, the aftereffects of trauma had typically been considered the “female” illness of “hysteria.” The symptoms of traumatization from WWI later forced Sigmund Freud to rethink his theories and begin to create a less gendered diagnosis.

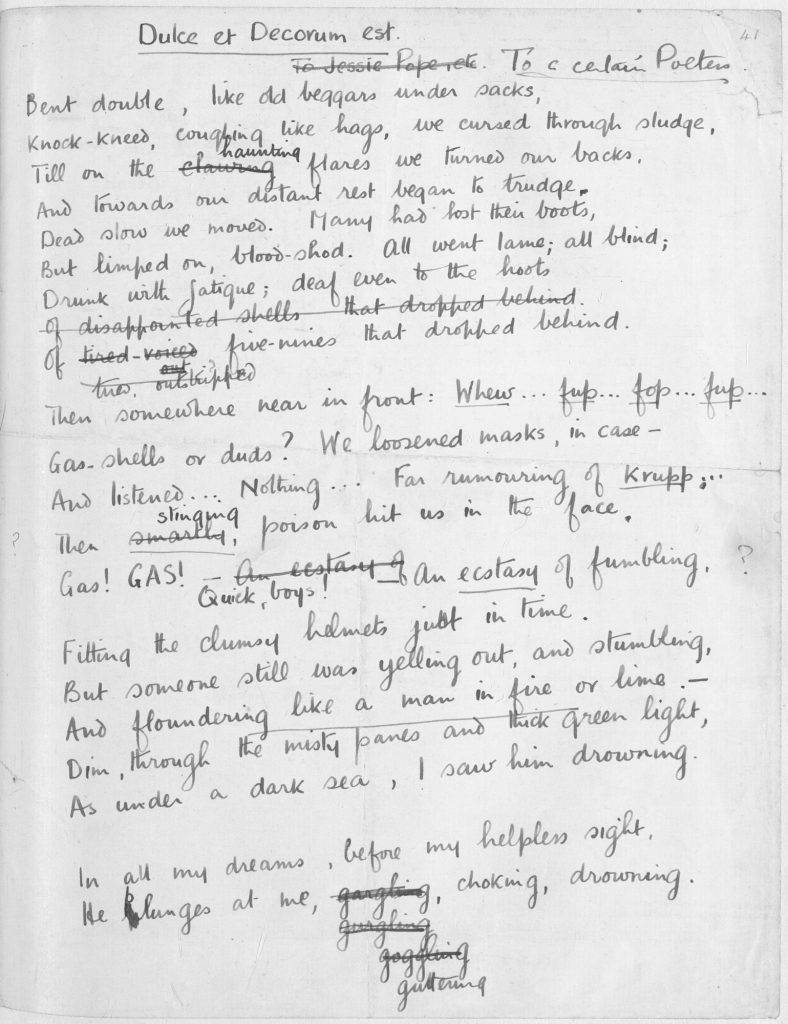

“Dulce Et Decorum Est” manuscript page 1

Courtesy of the British Library

Freud aside, Sassoon’s 1917 stay at the hospital coincided with that of a young officer who would become another influential poet: Wilfred Owen. Sassoon became a mentor for Owen, who went on to write “Dulce Et Decorum Est,” which reveals the harshness of war conditions and refutes the glory of dying in war. After the war, Sassoon continued to write, but Owen did not have that chance: he returned to the front and was killed a week before the Armistice.

During a time when media was skewed and letters were censored to disguise the war’s conditions, the young soldier-poets offered a rare honest picture. The adherence to realism in war poetry not only shaped literature’s development but also voiced the chaos and despair of war.

While both Sassoon and Owen were males, don’t worry: you can read the excellent historical novels written by contemporary author Pat Barker that feature some of these individuals. Taking on themes of gender in addition to war and trauma, her Regeneration trilogy consists of the novels Regeneration, The Eye in the Door, and The Ghost Road.