By Harriet Shenkman, Ph.D.

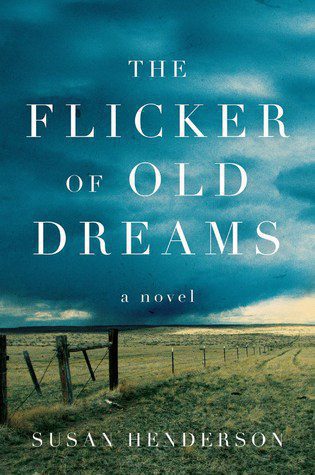

Being a poet and an aspiring novelist myself, I was exceedingly interested in the answers our two authors, Susan Henderson and Hala Alyan, gave to the questions I posed. Susan Henderson’s new novel, The Flicker of Old Dreams, is set in America’s heartland and is said to explore “themes of resilience, redemption, and loyalty in prose as lyrical as it is powerful.” In her debut novel Salt Houses, Hala Alyan writes about how we carry our origins with us wherever we go in “the exquisite prose of a poet.” Their answers give us sharp insight into the writing process in both genres.

You started out writing poetry. What made you switch to novel writing?

SUSAN:

SUSAN:

I started in poetry because it was my first love. From the beginning, I was captivated by the rhythm, repeating verses, and word play of Mother Goose nursery rhymes and Robert Louis Stevenson’s A Child’s Garden of Verses. I loved my mother’s Betty Carter records, especially the jazz scatting. I loved hearing other languages, not caring what the words meant, but finding pleasure in the what you can communicate with sound alone. I have always loved the way poetry can put me so deeply inside a moment. And yet, I felt constrained by the form. Or, rather, my voice did. I didn’t discover my full and natural voice until I switched to novel- and essay-writing.

HALA:

While I published first in poetry, my first experiences in writing were actually fiction, mostly short stories. I basically found myself hungrier for a longer form of storytelling, which is ultimately how this book was born. I found that the story I was trying to tell in Salt Houses was better served by prose than poetry, so decided to take a stab at it.

Which poetic skills can be used in novel writing? Do some subjects lend themselves to one genre or another?

SUSAN:

A good literary novel shares much with poetry: the distillation of language to its essentials, employment of all the senses, and either the juxtaposition of dissonant images or sounds to create a rumble of tension or conflict.

In the editing phase, I often pull sections of text out of my novel and play with them as I would a poem or a piece of flash fiction. I tighten each sentence—how can I say this with fewer, sharper words? Is this an active verb? Is this noun something I can see or taste or touch? I play with syllables. I play with the way one word can clack against another. I play with pacing. I might use staccato to show that my character is frustrated or out of breath. I might slow the tempo to say to the reader, notice this object, remember this moment.

And yet a novel cannot have the density of poems. This was the big learning curve for me when I changed forms. I had to remember not to cram too much into a sentence or a scene. I needed to let the sentences breathe. And I had to hold my reader’s attention for much longer; that meant letting the reader’s brain and attention rest a bit, without his having to put the book down.

HALA:

For me, if what I’m trying to say feels incomplete in poetic form, it means I should try my hand at telling it using a different genre. The scope of my debut is a multigenerational story of a family over many decades, so it felt apt that I’d need a genre that could accommodate the depth and length of that narrative. I very much rely on poetic skills in novel writing, particularly attention to detail, imagery, and even a thoughtfulness to beat and rhythm.

What elements are different in terms of the creative process?

SUSAN:

Poetry and flash fiction don’t require a plot. They might have an arc, or simply a swell, but they can be as contained as a single breath or a punch to the gut. But novels have more moving parts. Each character has his own desire and his own arc. And every scene in the novel must speak to the larger journey and the ultimate goal of that journey.

There might be a moment in a novel that reads like a poem. “The Piper at the Gates of Dawn” chapter in Kenneth Grahame’s Wind in the Willows, for example, is like a song. It’s a pause in the adventure so the reader can experience the fear and the what-ifs and ultimately the safety of a young, missing otter. But that scene feeds the larger journey; and after this rest, the quest continues.

HALA:

For me, it’s definitely the difference in instant gratification. That’s virtually non-existent when it comes to working on a longer project. When writing a poem, you have a product to show for relatively soon after, but with a novel, it can take years before the project even takes shape. I approach each genre very differently, often waiting to feel inspired before sitting down to write a poem, whereas I am more disciplined with fiction. I write thirty minutes a day, which helps me conceptually break down the project into thousands of little parts. That way, I feel a glimmer of that “gratification” when a paragraph is written!

SUSAN:

SUSAN:

Thanks, Harriet, for the thoughtful interview and the authors for their “distilled” wisdom, poetic and literary. I want to read these books!